OPINION: Looks shouldn’t determine success

January 8, 2020

With competitive, higher education becoming a societal norm for one’s future, you would think that the standards of determining success would be on a merit-based achievement system. However, new research suggests a correlation between “better-looking” students and students who excel in classrooms.

This research was performed by Barnard College economist Daniel Hamermesh and his colleagues. According to Christopher Ingraham, author of the Washington Post story that covered Hamermesh’s research, the overall findings are surprising.

“Prior research has shown that many factors of educational achievement on which policymakers tend to focus like teacher quality and program effectiveness, have a relatively small effect on student achievement,” Ingraham said.

During their research, Hamermesh and his associates broke apart and compared students’ performance and their physical appearance, separately. Specifically, they looked at two different pieces of data, a study in the United States and in the United Kingdom. The American study had a panel of undergrads who watched a video of the students and judge their appearance while the UK students had their appearances rated by their teachers. In both studies, students were rated above average and interestingly, Hamermesh confirmed that there is a bias of rating people as attractive.

When looking at the results for both parts in the study, it was found that “better looking children” achieve more academically. Ingraham described the possible reasons for this trend being the relationship “better looking” students have with their teachers. In fact, Hamermesh and his colleagues predict that the increased performance on standardized tests equated to about five months of additional schooling for “better looking” students over their average looking peers.

“They found some evidence that teachers report better relationships with the more attractive students, which explains some of the achievement gap,” Ingraham said.

Another trend is that students who were considered “unattractive” were more likely to report being bullied by peers. According to StopBullying.gov, bullying takes a toll on academic achievement, as grades and standardized test scores are more likely to be impacted. Also, school participation tends to drop because of the bullying, thus resulting in students missing class time and time with their teachers.

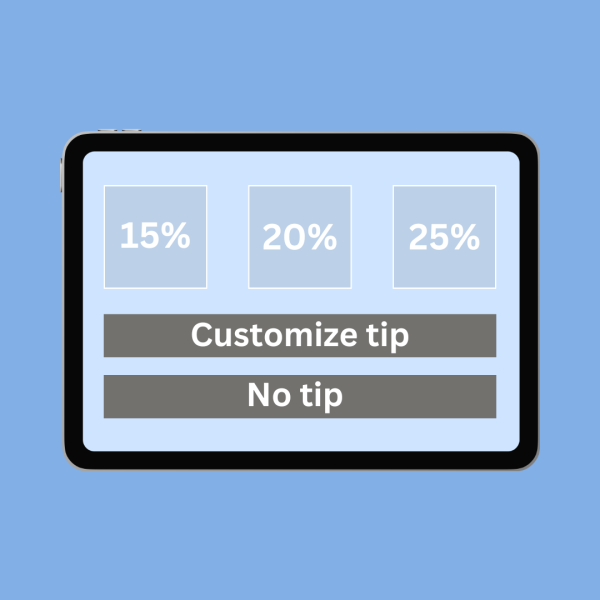

Susan Svrluga of the Washington Post wrote about Rey Hernández-Julián and Christina Peters’ investigation of that trend at the Metropolitan State University of Denver. They used student identification photos to rate the students’ physical appearance and again, students that were rated more attractive had a better performance in classes. But when looking at just online classes, the results were noticeably different.

“But when the researchers looked at courses that were online-only, they didn’t find the same benefit for men or women,” Svrluga said.

With the soaring rate of high school students pursuing higher education through the 21st century, the looks-to-success correlation cannot be ignored. I understand the importance of being presentable as an adult and to an extent, as a child or teenager. Adults, especially in the corporate world, have a responsibility to be presentable, and I believe that is important to companies and should be important to adults as well. In school, good hygiene practices are a must, but education should be the main focus teenagers have. “Less attractive” students, without a doubt, shouldn’t be subject to any abuse that may result in this trend. That would be immorally wrong and straight-up bullying, something I do not encourage.

No, this isn’t a baseless attack on the “attractive” in society, but, this is the calling out of a noticeable trend. The research performed by Hamermesh and his colleagues can appear to be a correlation, but when the performance gap in online classes shows a different correlation than regular classes, it’s important to call out this trend. “Less attractive” students may fear social interaction, so the actual pinpoint of the issue may be tough to tackle without further research and more testing. The findings of this research show that a deep look into the way teachers and students interact is necessary to the well being and fairness of future students.