OPINION: Schooling cultivates cheating

November 3, 2017

The kid who copies off of your test is supposed to be an unmotivated, intellectually inferior degenerate—but he is not. The kid you are shielding your answers from is at the top of his class—a straight-A student with a 4.7 GPA and Ivy League ambitions. This kid is dangerous; not because he represents the immorality of cheating, but because he shatters the logically dishonest presumption that cheaters are purely of their own doing.

Cheaters are the product of an academic model that values outcome over experience; their habits are not a manifestation of sub-standard ethics, but the fallout from a system of excessively competitive education.

In a 2012 survey of 24,000 American high schoolers by Rutgers University researchers, 64 percent of respondents admitted to cheating on a test, 58 percent admitted to plagiarism and 95 percent said they participated in some form of cheating before graduating, whether it was cheating on a test, plagiarism or copying homework.

Honors and AP chemistry teacher Dr. D’Meo said those statistics are “not surprising.” Cheating among top-tier students, Dr. D’Meo said, is largely a result of the times. “It’s cultural pressure and the narrative they’re fed by friends and mentors.”

English teacher Ms. Dunphy, who has taught for 27 years across four districts, echoed the timeliness of trends in cheating. “The cheating rise in the last 10 years is big,” she said. “It’s pervasive.”

As the landscape of cheating has grown, so has the measure of its moral gray area. Though most students the Wire spoke to acknowledged that cheating is wrong, they had a tendency to justify their habits as a necessary evil. Most of the students were comfortable granting considerable latitude to the academic dishonesty of their peers.

“It’s disturbing how accepting people are of it,” Ms. Dunphy said.

The appreciable confidence of the cheating class, Dr. D’Meo said, has much to do with how easy outsmarting the system can be. “Cheating is hard to prove,” she said. “Very few kids get caught.”

The ability of teachers to accept and respond to the realities of modern cheating, however, Dr. D’Meo said, determines how prevalent cheating will become in a classroom.

“If you don’t think students are collaborating, you’ve been teaching for five minutes,” she said. “You’re never going to get it to be 100 percent honest, but it is my responsibility to prepare students to prevent cheating.”

Ms. Dunphy agreed about the role teachers play in curtailing academic dishonesty, but also noted that such efforts have added “a different level of stress to teaching.”

“We didn’t go to college for a gold shield,” Ms. Dunphy said of teachers. “It’s a lot of work to get around cheating.”

Though these attempts by teachers to uphold scholastic legitimacy in their classrooms are noble, they treat symptoms rather than the disease. Creating multiple versions of a test or screening student work through sites such as Turnitin.com may currently be the best defense teachers have against academic dishonesty, but such initiatives fail to address the ailments of a culture that necessitates cheating for so many students.

Ms. Casais, the Instructional Supervisor of English, Reading and Libraries, noted that while statistics regarding cheating among teenagers are indeed startling, most instances of academic dishonesty are “not coming from a place of malice.”

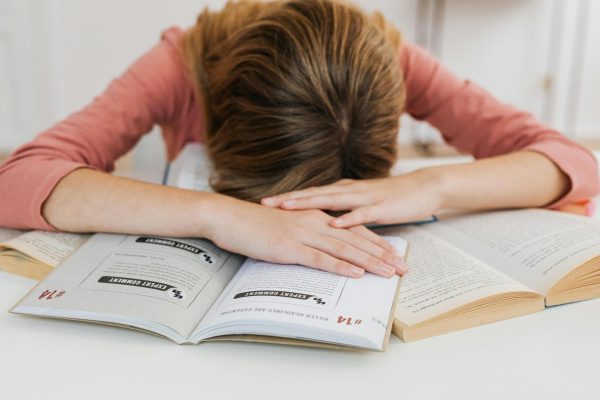

Dr. D’Meo agreed with that sentiment. “They’re all good kids,” she said. “They’re just exhausted.”

Students the Wire spoke to said that finding an easy way out is often the only way they feel able to meet unreasonable standards. Though the origin of those standards remains in contest, the repercussions of that seemingly insurmountable pressure are on full display.

Stress and anxiety among students is rife, Ms. Dunphy said, especially in her AP classes. “I have students who are afraid to bring home Bs,” she said.

Dr. D’Meo identified the errant messaging many students receive about higher education as a factor contributing to that stress. “Students think they need to be well-rounded,” she said. “Colleges want a well-rounded class, not well-rounded students. They want passion and grit.”

The powers in education must recognize, consequently, that cheating ought not be viewed as pompous bravado, but as a collective cry for help. High-achieving students do not put their academic record on the line because a few extra points makes them happy, but because the system has conditioned them to value those points over integrity.

To combat cheating effectively, educators must construct an atmosphere where rigor does not inherently negate the character schools try to instill in their students. Students have to be comfortable with earning Bs and Cs; they have to learn that personal happiness is more important than being well-rounded; they have to accept that failures are natural. But they need help to get there.

“Students do the best they can,” Dr. D’Meo said.

It is about time schools showed students that their best actually is good enough.