OPINION: Why Americans can’t write well

May 9, 2017

Despite an ambush of standards meant to regulate student proficiency in English, the overwhelming majority of American high schoolers are horrible writers. Worse than the essence of this pandemic linguistic incapacity itself, however, is the reality that neither students, nor their teachers, are fully to blame for it. They are—in a global society where effective communication is critical—the byproducts of an ill-conceived American system that guts rudimentary skill sets and fosters resentment toward feigned educational progress.

The most recent perpetuation of the increasingly standardized approach to education, the Common Core, is largely to blame for this failure, acting as an accessory to the plague of often misguided English classes. The standards, targeted toward critical thinking and testability, are in many ways characteristic of a new approach to teaching language arts.

Since the introduction of Common Core Standards in 2009, forty-two American states and the District of Columbia have fully adopted the guidelines and, in the process, condemned their students to an unequivocally subpar education in writing. Like national educational initiatives that preceded the Common Core—take the George W. Bush-era No Child Left Behind, for example—current standards similarly miscalculate existing student proficiency and provide little opportunity for teachers to promote growth.

Since the introduction of Common Core Standards in 2009, forty-two American states and the District of Columbia have fully adopted the guidelines and, in the process, condemned their students to an unequivocally subpar education in writing. Like national educational initiatives that preceded the Common Core—take the George W. Bush-era No Child Left Behind, for example—current standards similarly miscalculate existing student proficiency and provide little opportunity for teachers to promote growth.

In a 2011 report authored by the National Center for Education Statistics, the most comprehensive study conducted in the last decade, only 24 percent of 12th graders were proficient in writing, and just three percent were labeled as “advanced proficient.”

While it has become standard to blame texting or social media for the deterioration of the American lexicon, the truth is that students are not taught the basic constructs of proper English nor the lucidity and power that defines quality writing.

Long gone are the days when students would diagram sentences or identify parts of speech. Stamping such practices as unnecessarily elemental and juvenile, standards shifted toward evidence-based analysis meant to target problem solving, yet simultaneously overlooked the value of rote comprehension.

While analytical skills are undeniably essential components of well-rounded writing, students lack the fundamental tools necessary to effectively express their ideas. A student has to be taught how to add before he can do algebra, yet students are being asked to write college-level arguments without even a basic understanding of sentence structure and style.

Rather than focus on the manual skill inherent to effective communication—the ultimate goal of writing—standards have forced teachers to steer students toward multi-step questions with dubious answer choices and formulaic writing that bores young writers and smacks the principles of literature in the face.

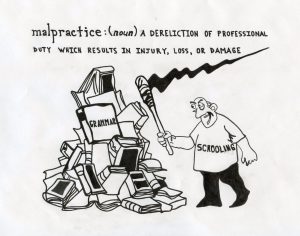

Inundated with students unprepared for the rigor and expectation of their English classes, teachers are limited in reparative scope. Faced with years of educational malpractice, it is impossible for them to reverse years-old habits and promote grammatical understanding while still preparing students for assessments used to rate, fund and study public education.

This mechanical regurgitation of tired and baseless English expectations has—predictably—birthed a newfound contempt for literature. The rinse-and-repeat ad nauseum of assigned readings and corresponding questions is not just horribly dull, but also an inhibitor of the creative and thoughtful humanities that good writing relies on.

Never in the history of quality literature has an author referenced the ideologies of standardized education as a motivating or remotely advantageous factor in the pursuit of literary prowess. A love for reading and writing and an unwavering conviction in the power of language serve as the true index of linguistic mastery.

Test questions, passionless monotony and the dissociation of basic English from analytical thought hold the power to eviscerate writing. Propagating a system that relies on highly-contested assessments and misguided expectations does not just rob students of literary fervor and competency—it robs them of their voice.

That is morally repugnant and it begs action.

Although analytics and depth steer effective writing, students need to be taught the basic tenets of the English language first if America wants to reverse this distressing diversion to incompetence.

The forces governing ill-conceived English curriculums must bend to the expertise and experience of the people actually doing the work. Engaging in conversation with teachers (the professionals who understand the problem’s origins best) and with students (the people most familiar with the patronizing fallout of this malpractice) is an essential precursor to revitalization.

Writing is not about profits or formulas; it is about understanding and communicating the complexity of the human condition. It is the lifeline of the silent and the megaphone of the vociferous.

It is not something to warp to the perverted whims of those who exploit academia for feigned prestige and destructive prominence.