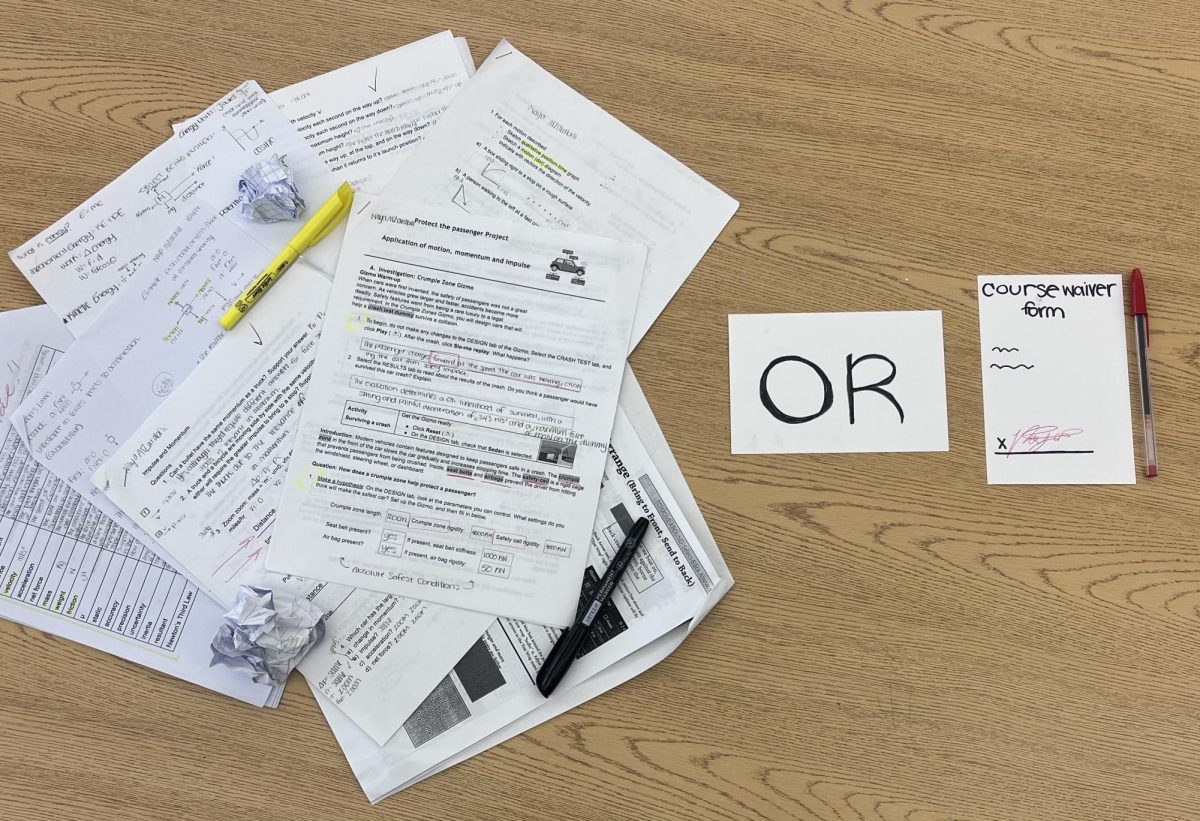

In 2022, West Essex introduced the course waiver form: a seemingly simple document that allows students to take on “challenges they deemed themselves ready for, despite not checking every box. Three years later, the number of waivers submitted has surged, with over 400 new waivers being placed. The “course waiver form” is no longer a quick fix to minor inconsistencies in requirements—it’s a pattern of quiet loopholes.

In its first year, 2022, 269 students submitted the form; that number grew to 343 in 2023, then 470 in 2024. For the 2025 school year, more than 630 submissions were recorded.

The most cynical explanation would be that students are slacking off or that they have grown more reliant on shortcuts such as the waivers. They’re not willing to put in the effort during foundational classes, instead relying on a form to skip ahead. But that theory ignores the reality of student life today. West Essex is consciously a high-performing and competitive school district. Students are expected to manage and balance advanced coursework, extracurriculars, part-time jobs, and the relentless pressure of college admissions. The rising number of waiver submissions may reflect the opposite of laziness—it may signal an environment where students feel compelled to accelerate, even when they’re not fully prepared.

Still, the purpose of prerequisites deserves a closer look. These aren’t arbitrary barriers; they exist to ensure that students build the knowledge necessary to succeed at the next level. Waiving into AP Physics without comprehending Algebra II, or jumping into APUSH without a firm grasp of historical writing, isn’t just ambitious: it’s risky. The consequence of being underprepared is often invisible on the surface—until stress, burnout, or academic underperformance catch up.

What makes the trend more concerning is how easily the waiver process is approved. With most forms accepted without question, prerequisites begin to lose their meaning. When nearly anyone can take the alternate path, it becomes the default.

This is especially relevant in the context of AP classes. These courses are designed to match, or at least mirror, the rigor of college-level academics. They are not meant to be casually entered, nor are they intended to signal intelligence or worth. Yet the growing belief among upperclassmen is that the more APs on a transcript, the better the student looks. And in an already competitive district, that belief has serious weight.

In its current structure, the waiver form offers students freedom, but without direction. It opens with a lengthy warning urging careful consideration, but there’s no guarantee anyone reads it, and no system in place to make sure they do. There’s no formal evaluation before submission, which would be used to assess whether a student is truly prepared for the class they’re entering. Instead, the responsibility falls entirely on overwhelmed teenagers trying to keep pace in a high-pressure environment. This easily comes off as a hands-off approach masked as an opportunity.

This is not to say that the waiver form is inherently harmful. When used thoughtfully, it can be a valuable opportunity for motivated students to challenge themselves. The number of students who have dropped down to their recommended level at the first progress report has also gradually declined.

West Essex prides itself on academic excellence, but true excellence isn’t about the number of AP classes a student can list. It’s about ensuring they are equipped, supported and genuinely ready to take on what they sign up for. There is no evidence that they can’t coexist with the form. However, it is a matter of responsible personal reflection.

If West Essex is serious about maintaining the integrity of its academic standards, the answer isn’t simply to close the gates tighter—it’s to restore purpose to the process. That could mean rethinking how waivers are approved, introducing clearer expectations or simply encouraging students to consider why they’re pursuing a course in the first place. Because when nearly everyone is bypassing the prerequisites, the issue may not lie with the students or the classes, but with a system that no longer stops to ask whether it’s serving them well for their education and mental health.