In the United States, the word trauma has undergone an extreme transformation. Once reserved for war veterans or victims of extreme violence, it is now commonly used to describe a wide range of ordinary, though painful, human experiences. More and more of life’s inevitable discomforts are dramatically labeled as traumatic, and as the word spreads, so does confusion about what the word actually means and where it should be used.

In recent years, this problem has been brought up through the trend of self-diagnosing. Social media platforms like TikTok and Instagram are flooded with content creators explaining symptoms of complex PTSD, anxiety disorders and childhood trauma. Many celebrities film “trauma test” videos to prove they’ve had a traumatic experience, or even childhood. They promise clarity to those who feel misunderstood and create feelings of sympathy and understanding between the creator and their audience. However, in doing so they also blur the line between medical reality and emotional storytelling.

According to psychologists, trauma refers to an experience so overwhelming that it disrupts the body and mind’s ability to process it. It is often sudden and/or life-threatening and leaves a deep, lasting imprint. But when the term is expanded to include everyday hardship, its meaning is diluted, and its consequences become cultural.

In The Coddling of the American Mind, authors Greg Lukainoff and Jonathan Haidt argue that this shift is not uncommon. It’s part of what they call “the Great Untruths”- ideas that feel compassionate when said but may, in fact, be harmful. One of those untruths is, “What doesn’t kill you makes you weaker.” Instead of pushing through a difficult situation, people will give up before even trying to persevere,

The authors claim this teaches young people that discomfort is dangerous and growth can only happen in perfectly safe, perfectly controlled environments. It discourages risk, struggle and even conversation, framing them all as potential sources of harm.

People are quitting schools, jobs and relationships at the first sign of stress. Some are retreating into identities formed by their “diagnoses”, seeking validation but instead accepting limitations. Others believe that healing means avoiding all discomfort rather than facing it. This isn’t a weakness. It’s the product of a culture that values validation far more than resilience.

More people must recognize that hardship does not always equal trauma. Sometimes it is just hardship. And though unpleasant, those difficult moments are what teach you how to improve and become a better version of yourself. Breakups can teach boundaries and inspire self-reflecting. Arguments and job rejections strengthen critical thinking. These moments are not pleasant, but they are part of life- and they do not require a clinical label to be valid.

None of this means people should be silent about pain or push through it without care. It means learning to label difficulties accurately. Mental health awareness is important– as is endurance. But they are not the same, and knowing the difference is what makes recovering possible. When society treats every unpleasant feeling as pathological, it robs people of the chance to learn from the normal challenges of living.

To refer to simple hardship as trauma invalidates genuine struggle. Not every wound must be seen as a scar, not every challenge is the end of the world and not every moment of pain is something to be feared. What doesn’t kill you can make you stronger. You just have to let it.

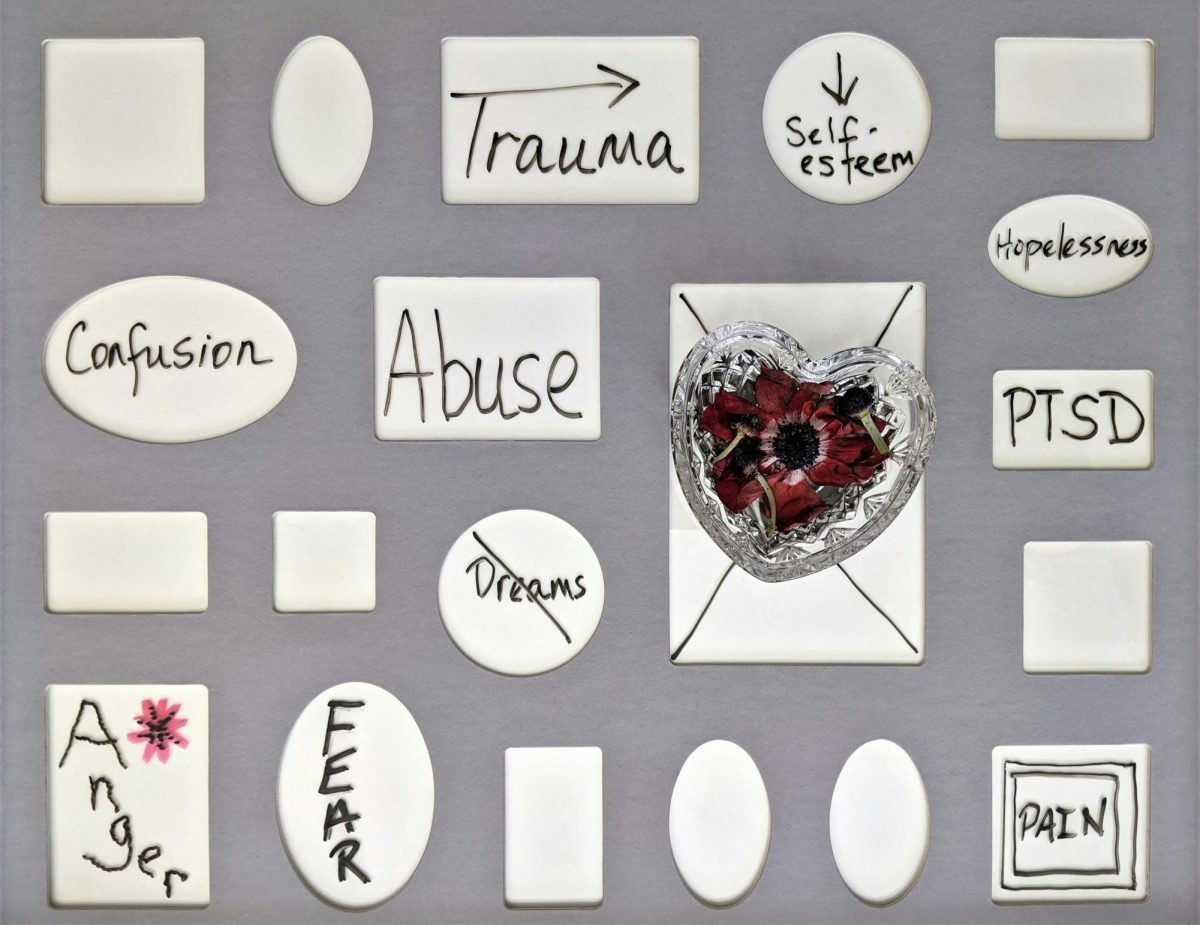

Photo credit: “Abuse. Ongoing trauma. Low self-esteem. Boxed in by pain. Fragile hearts, broken and darkened” by Susan Wilkinson