OPINION: Red Ribbon anti-drug campaign grossly oversimplifies a complex issue

Up until recent morning announcements, I had no awareness of Red Ribbon Week, which focuses on preventing drug use amongst children and teens. A noble cause, right? Regardless of how righteous drug use prevention may be, the attitudes of Red Ribbon Week and especially the school sponsored daily announcements, are crushingly one-sided and biased. I am not some crusader in favor of drug use, but in order to understand America’s addiction epidemic, I need to widen your perspective and extend your empathy.

First, what is the Red Ribbon Campaign? Formalized in 1988, and headed by National Family Partnership, the Red Ribbon Campaign (RCC) was founded in 1985 to honor Enrique (Kiki) S. Camarena, a DEA special agent who was murdered by cartel members. It gained national recognition when President Ronald Reagan and First Lady Nancy Reagan became honorary chairpeople for this cause. So where’s the issue with an anti-drug movement established to memorialize a heroic DEA agent, backed by the First Family?

Well, the Reagans’ stance on drug abuse nearly mirrors the same neglectfulness of RRC. As FLOTUS, Nancy Reagan made drug abuse her primary cause, leading the “Just Say No” movement, which encouraged kids to “Just Say No” to drugs. While America’s youth pledged against drug use, Ronald Reagan was pushing for the implementation of mandatory minimums on prison sentences for drugs, now notorious for its racism. Mandatory minimums legally mandate any person found guilty of a crime must serve at least the minimum sentencing stated in the legislation. That’s all very well and good, but what makes them racist? While black Americans only compose about 12 percent of America’s population and 38 percent of those arrested for drugs, they are disproportionately convicted and imprisoned for drug offenses — with black Americans constituting 59 percent of convicted drug offenses and 74 percent of those caught are sentenced to prison. The penalties for drugs more frequently used by low-income people of color, such as crack cocaine, had stricter minimums than those used by wealthier white people, such as powdered cocaine. Drug prevention programs are vital, but discriminatory enforcement of reactionary legislation, as the honorary Red Ribbon chairperson Ronald Reagan did, only serves to worsen America’s struggle with addiction.

In the 40 years that mandatory minimum sentencing has been implemented, the addiction epidemic has only worsened, thus proving their ineffectiveness. In that time, a new menace has arisen and drastically increased the number of overdoses and adults with addiction: synthetic opioids.

In 1996, a wonderdrug hit US markets: OxyContin. From hospice patients with late stage cancer to those healing from broken bones, an Oxy prescription was your cure-all. But don’t just take my word for it — listen to the experts, such as this excerpt from a 2001 Purdue Pharmaceutical pain management guide:

“Some clinicians have inaccurate and exaggerated concerns about addiction, tolerance and risk of death. This attitude prevails despite the fact there is no evidence that addiction is a significant issue when persons are given opioids for pain control.”

Despite OxyContin being in the same drug class as heroin and crack cocaine, two notoriously addictive drugs, Purdue kept its unwavering stance that “there is no evidence that addiction is a significant issue when persons are given opioids.” Purdue maintained that less than one percent of patients prescribed opioids developed an addiction, thus deceiving both doctors and patients.

This, partnered with their aggressive marketing campaign in which sales representatives were showered with lavish rewards for prescribing opioids to patients who did not need them, sent America hurtling into the opioid epidemic. When OxyContin was approved by the FDA in December of 1996, it made $48 million of sales. In 2000, after only four years on the market, OxyContin sales had surpassed $1.1 billion. By 2004, OxyContin became a leading drug of abuse in the US. How did OxyContin make billions in profit as well as become a primary addictive drug in the US in only eight years?

The answer is simple: to minimize any patient pain, OxyContin should be prescribed. Drugs intended only for late stage cancer patients in extreme pain became overprescribed by physicians as antibiotics. But what’s the harm, when “there is no evidence that addiction is a significant issue when persons are given opioids.” The answer is also more complex. Over the years 1996 until 2001, Purdue held 40 all-expenses-paid symposia in which hundreds of doctors, physicians and nurses would attend. These symposia drastically influenced the prescribing choices of the medical professionals in attendance, by overstating the benefits of OxyContin and horribly, unethically minimizing its addictive properties.

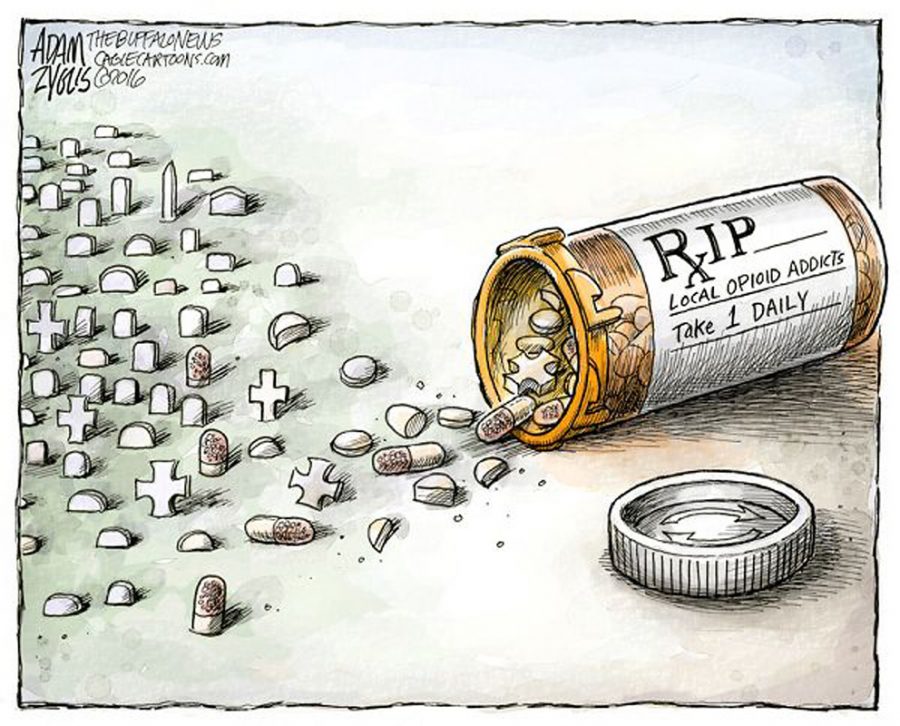

So what’s the point? What on earth does this have to do with Red Ribbon Week? Red Ribbon Week paints addiction as the addict’s fault. After all, they decided to “just say yes” to drugs, when saying “no” should have been so easy. But this oversimplification negates the truth of the American addiction epidemic. Those prescribed with drugs such as OxyContin were unaware of their addictive natures. Doctors who they trusted and who had believed the misinformation campaign led by big pharma companies, wanted to just help their patients manage chronic pain. The road to addiction was paved in the good intentions of many misled medical professionals.

Addiction is never the sole fault of the addict, as Purdue and the Red Ribbon Campaign may lead you to believe. It is not some moral, mental or personal failing. Addiction is a disease and it only worsens when blame is placed on the addicts. Instead of stigmatizing addiction, we need adequate infrastructure to help facilitate recovery and we need criminal prosecution of big pharma. Addiction can be prevented, not by encouraging teens to just say no, but by confronting the ugly history of the American addiction epidemic.

Photo Credit: “Opioid Epidemic” by DES Daughter is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0